As a designer I’ve often wondered what are people doing if they’re not design thinking? Can anyone be a design thinker? And if so, does it put designers out of a job?

Design thinking? I love it! What is it?

There are piles of words written on what design thinking is and how it works.

I’m not going to add to it.

Depending on what you read or who you listen to, it’s the secret sauce of innovation, it’s flawed for any number of reasons, or it’s just plain corporate jargon BS.

Either way, now that it’s here it’s not going away. The concept of design thinking is firmly embedded in the lexicon of business, government and NGO’s—and is in high demand as a service.

Although groups like IDEO and the Stanford d.shool are synonymous with design thinking, they didn’t invent it (they actually didn’t even coin the term, it emerged way back in the 60’s). However, they have popularised the concept, and helped reposition the purpose and value of design in the common consciousness, helping separate the noun from the verb and the process from the aesthetics.

But who is a designer thinker? And who is not?

I (design) think, therefore I am?

Almost 20 years ago I graduated with an Honours Degree in Graphic Design, and have been working in the design industry ever since. Here’s an awkward graduation photo. So many random hands.

In my career I’ve seen the title of my degree go from graphic design, to visual design, to visual communications and back again. I’ve watched as people anoint themselves brand designers, UI designers, UX designers, service designers, human-centred designers and design thinkers. The list goes on.

What’s in a name?

In my opinion (and not only my opinion), not much. Design is a messy process, and sometimes it’s hard to concisely pin down designers do, let alone articulate it. The best explanation is that designers are problem solvers, but you’ll rarely hear them say that (for fear of sounding like a wanker). You’re more likely to hear them reach for the tangible outputs—websites, logos, chairs, buildings—to explain what they do, rather than how or why.

However, over the last few years as the concept of design thinking as a problem solving tool has become more prevalent, clients are becoming more interested about what processes we use (do you use double-diamond?), or what our opinion is on design thinking.

A couple of years ago I sat on a panel with communication design educators in secondary schools who talked breathlessly about design thinking and wanting to know my opinion as a practicing designer. My answer was less than exciting. Why? I didn’t know if I was actually a design thinker.

Internally I was feeling irrelevant — I felt like I’d had the designer-rug pulled out from beneath me, that while I’d been honing my knowledge, craft and skills over here, a ‘new’ kind of design had emerged over there.

Outwardly I was skeptical: isn’t design thinking just a new label for what we—trained designers—have always done?

Haven’t we always tacitly used the design process—some form of discover, define, develop, deliver (or investigate, ideate, implement and iterate – depending on what your favourite letter of the alphabet is)?

Haven’t we always based our creative responses to challenges and opportunities on empathy? By understanding the people we are designing for (now known as humans) — their wants and needs?

This sounds like some BS right? Turns out I wasn’t alone in my skepticism.

Was this just a passing trend? At Alto we’ve never been one to follow trends, and to just suddenly add design thinking to our service list would feel like we were jumping on the band-wagon. But were we missing an opportunity here to claim what is already ours, solely out of stubbornness?

Do we do design thinking? We had to find out. It was excursion time.

The co-design symposium

A while back Mark and I attended a ‘co-design symposium’—an all day event featuring workshops for “all things co-design, design thinking and human-centered design… the symposium promises to bring together the community who will drive the future of this potentially game-changing field of design.”

We rubbed shoulders (literally—there was a loosening up exercise where we all rubbed each others’ shoulders and hummed ?) with representatives from private, government and non-government organisations, all curious about design thinking.

What did we find? Two things:

Firstly, we found that our skills, methods and frameworks that we had learned and used either formally, tacitly or intuitively over our careers were infact design thinking (we just didn’t call it that or use as many post-it notes) Phew!

Secondly, we found an auditorium full of intelligent, passionate and driven people frustrated with the status-quo and wanting to know how they can bring design thinking to their organisations for innovation and change.

This got me thinking. These people aren’t stupid. If they’re not thinking like designers, what are they doing? What is the opposite of design thinking, anyway?

The opposite of Design Thinking

Based on our experiences and conversations with other symposium-goers on the day, here’s what we think is not design thinking:

Acting on existing knowledge, assumptions and biases

Doing things the way they have always been done and expecting a different result (actually not Einstein’s definition of insanity as it turns out)

Acting impulsively or on instinct alone

Doing without thinking or planning

Accidental, unintended or unplanned results

Doing nothing at all and leaving to chance

These outcomes occur when:

- there is a lack of time, and a solution is rushed

- solutions are developed too soon or for the wrong problem

- solutions are developed that are ‘looking for a problem’

- people falling in love with their own ideas without finding out if it’s actually what people want or need (which is often a result of point 3)

- when people are afraid to (or not able to) speak up or challenge an idea

- not knowing what to do, so doing nothing

All of these scenarios have similar hallmarks but to different degrees:

- Not correctly diagnosing or defining the problem

- Not understanding the audience or consulting the right stakeholders

- Not testing and validating with the audience

What is the result? Failed projects and wasted time and money.

If this is the opposite of design thinking, then you can understand why design thinking is so attractive. It promises a silver-bullet methodology to problem solve in all three of these scenarios, greatly increasing the chances of a successful—and maybe even innovative—solution.

And as a bonus, it sounds sexy because ‘design’.

So… now that everyone knows the big secret about design thinking, and all you have to do is follow the step-by-step recipe, are designers out of a job?

Not. So. Fast.

If anyone can design think, what becomes of the designer?

Design thinking is marketed as a method of problem-solving that can be learned and used by anyone.

There’s any number of resources on the internet that can skill you up on the principles and methods that will get you solving problems like a designer.

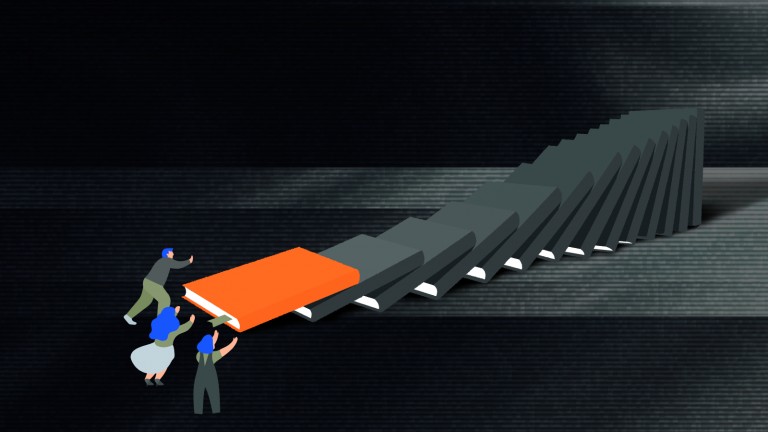

However, there is criticism that the how-to manuals for design thinking underestimate and oversimplify the design process. And rightly so—just because you’ve read a book on karate it doesn’t make you a black belt.

“Collecting dots, connecting dots”

As much as design thinking diagrams make it look simple and logical, design is as much mess as methodology.

Designers are adept at pattern finding amongst the chaos—or as Seth Godin loves to say, not just ‘collecting dots, but connecting dots’. The design process generates buckets of data, ideas and viewpoints—that’s great—but it’s what you do with it, sorting the information, recognising patterns, developing insights and creating outcomes that turns design thinking into design-doing.

“Design is thinking made visible”

Another criticism of design thinking is the lack of action after the warm-fuzzies of the workshop/s have worn off. Successful design solutions require two parts: thinking and doing.

When renowned designer Saul Bass said “Design is thinking made visible” he wasn’t talking about post-it notes, he was referring to the key skill in every designers toolbox – making design thinking tangible, testable and shipable.

A problem isn’t solved by just thinking about it—it’s solved when the thinking has been converted into doing. It’s what’s left after all the post-it notes have gone that matters.

Design thinking is better together.

If anything, the concept of design thinking has helped reposition the role of the designer as a facilitator (or guide) of the co-design process, not the genius that will magically solve the problem.

Often all the answers are in the room or in the research, not in the head of the designer. As an external party, designers have the benefit of the outsiders perspective—being able to challenge assumptions and ask the ‘dumb’ questions without fear or favour.

…

“If you can design one thing, you can design everything”

All those years ago when I was a graphic design student, we studied the design pioneers—the Vignelli’s, the Eames‘ et al.

Those legendary designers were polymaths—working across multiple domains of design, from communication design, brand visual identity design, product design to environmental design and more. They didn’t limit themselves to a particular title or discipline—they were designers—thinkers and doers. Full stop.

One of Vignelli’s famous sayings was “If you can design one thing, you can design everything”.

As a graphic design student I never really understood this, I thought it meant that you needed technical skill and knowledge in a vast number of disciplines. Something only a design genius would be capable of.

Now, I understand that if you have the methods to solve a problem, then you can solve (almost) any problem. You don’t have to be a genius, you don’t have to have all the answers. But to get the best outcomes you need to be experienced in the method—the thinking and the doing.

Whether that method is called design thinking or just plain-old design, as designers it’s what we’ve always done, just rebranded and repositioned for a new market in a new millennium.

The upshot is that by making the practice of design thinking more popular and accessible, design is no longer perceived as an exclusive process reserved for experts or geniuses. That doesn’t make the designer redundant, it makes them more relevant than ever.

Design has now been reframed as an inclusive and collaborative process—for all to participate, contribute and benefit from—resulting in a huge leap forward for the design agencies and their clients.

That’s a win for everyone, design thinkers, designers and non-designers alike.

Now, who’s up for a shoulder rub?